DSF’s Producing Artistic Director David Stradley will be directing this summer’s THE COMEDY OF ERRORS. He’s writing a blog entry each month to let DSF’s fans into the creative process behind the production.

Over the last few weeks, I’ve started the work of compiling the edited script of The Comedy of Errors. The process of cutting of the script is the first step in the production going from the ephemeral land of my imagination to the very practical reality of what will actually appear on the stage at Rockwood Park.

I really love cutting the script. But first, some of you may ask, “Why do you cut the script? Isn’t Shakespeare the best writer in the history of the English language? Don’t you want the audience to hear every one of his glorious words?”

My answer, to paraphrase Brutus in Julius Casear, is “Not that I loved Shakespeare less, but that I loved our audience more.”

Our Summer Festival is a fun, informal, family-event. Most of Shakespeare’s plays, uncut, would last between three and hour hours. Nothing says outdoor summer fun like being at Rockwood until midnight! So, we cut to get the plays down to a more manageable length of between two and two and a half hours.

It’s also very likely that Shakespeare’s plays weren’t even performed uncut in his time. The prologue of Romeo and Juliet summarizes the action the audience is about to see in “the two hours’ traffic of our stage.” Yes, Shakespeare’s actors probably talked a lot faster than contemporary actors (CLICK HERE for an article about actor Mark Rylance’s thoughts about pace in Shakespeare), but not fast enough to turn 210 minutes into 120.

And then finally, I’ll admit it, every once in a while in Shakespeare there are some words or some phrases or some references that just don’t make much sense to a modern ear. So, cutting allows you to do some preemptive smoothing of the experience for the audience.

So, that’s why we cut the scripts. Mainly for length, and a little bit for comprehension.

Now, back to why I love cutting the script. It’s an immersive deep dive into the world of the play and an exploration of the choices that Shakespeare made when writing the script. I work a lot with young playwrights (middle school and high school students), and enjoy asking them lots of questions about their scripts in development. “Why did you do this?” Based on what you wrote, I’m guessing this theme is important to you? Is that right?”

When I start cutting a Shakespeare script, I imagine having a conversation with my friend Will, asking those same kinds of questions I ask young playwrights. I try to imagine his answers. I always learn things. With The Comedy of Errors, it’s not hard to make the leap that a play about two sets of identical twins has a lot to say about identity. But in cutting the script, I’m realizing how much action and references there are to merchants and business transactions. Shakespeare’s father was a merchant, a glove-maker. Shakespeare himself was obsessed with business, as he was part-owner and operator of the acting companies he belonged to. I could see Shakespeare at the beginning of his writing career (The Comedy of Errors is an early play) musing about whether his identity would always be wrapped up in the world of business transactions, and how that intense focus on business would impact his creative identity.

I’m also realizing how compactly Shakespeare wrote The Comedy of Errors. It’s his shortest play by far and one of only two that follows Aristotle’s rules of dramatic unity – taking place in one location and in the course of one day. A lot of it is also written in rhyme. So, you start realizing very quickly that there isn’t that much to cut and that if you do cut, you can very easily start doing damage to the efficient structure Shakespeare worked to create – or totally screw up the rhyme scheme. While DSF’s Hamlet had to be cut with a machete, the work on The Comedy of Errors is being done with an exacto knife!

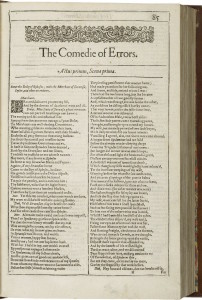

I use the text from the First Folio when I work on a Shakespeare play. The First Folio was the earliest published version of Shakespeare’s complete plays, one copy of which will be on display next fall at the University of Delaware (CLICK HERE for an article about the exhibition). I like the First Folio because it feels like the closest we can get to what Shakespeare was actually thinking when he put quill to paper. And the First Folio text just looks rougher than contemporary published editions, reminding me and the actors that these plays were not born in a polished, perfect state. They were born in the heat of the creative act, and we want to try to capture that energy.

Here’s how the start of one Antipholus of Syracuse’s monologues looks in the First Folio:

He that commends me to mine owne content,

Commends me to the thing I cannot get:

I to the world am like a drop of water,

That in the Ocean seekes another drop,

Who falling there to finde his fellow forth,

(Unseene, inquisitive) confounds himselfe.

And here’s the same section as published in the Arden Shakespeare (2nd Series):

He that commends to mine own content

Commends me to the thing I cannot get.

I to the world am like a drop water

That in the ocean seeks another drop,

Who, falling there to find his fellow forth,

(Unseen, inquisitive) confounds himself.

It’s not a big difference, but sometimes seeing a word with a long spelling (extra “e” at the end) or another punctuation choice can lead an actor to do something different with the text. For instance, in the First Folio, the text is one sentence, one tumbling thought. In the Arden edition, it’s two sentences. An actor using the Folio text may decide that the character is not quite as in control of his thought process because of the different punctuation.

One of the other things I like about cutting and formatting the text is the laborious nature of it! Ever since I learned how to format a book, it’s been a great hobby of mine. I cut and paste a digital edition of the text from the internet, and then go through line by line – changing formatting, adding full spellings of character names, cutting and pasting lines, etc.. It reminds that when the scripts were originally shared with Shakespeare’s actors that a scribe had to copy each version by hand, line by line. It was a labor of love. And took some time. I enjoy that “slow burn” time with Shakespeare’s words that comes when you cut a script.

Finally, the other fun thing that comes while you cut a script, is spending time thinking about the actors who might play these roles. We’ll be scheduling auditions in January, and, as I’m cutting, I’m thinking about what qualities would be best for actors in different roles and what roles might be doubled. In The Comedy of Errors, there are two characters, the Duke and Egeon, who only appear in the first and last scenes. And another character, the Abbess, who only appears in the last scene. Well, that’s not an efficient use of an actor’s time! So, are there creative ways to double an actor in another role in order that they might be a more engaged part of the production?

Often, I’ll have one thought about how an actor might play two certain parts in the play, but then an actor will come into an audition and prove there is an entirely different way of doubling. That’s the fun we’ll start having next month in auditions. And because of the time I’ve spent cutting the script, I’ll be well prepared to jump into the text and collaborate with the actors during their auditions.

The Comedy of Errors Director’s Blog – Other Entries

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

January 2016

November 2015